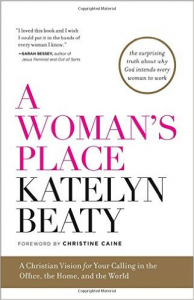

Every once in a while I come across a book that makes me think, Wow, this author really gets me. Those books give expression to the longings and desires I am unable to articulate and plunge into the depths my soul. Katelyn Beaty’s work A Woman’s Place: A Christian Vision for Your Calling in the Office, the Home, and the World is one such book.

Until recently, Beaty was the print managing editor of Christianity Today and co-founder of the Her.meneutics blog. She wrote this book to bring the conversation about work to evangelical women. Although in the past ten years evangelicals have begun to revisit and champion the inherent goodness of work, these conversations have rarely given attention to women’s role in work. Yet over 70 percent of women work in some capacity, and women outnumber and outperform men in many professions and places of higher education. Women are a growing and unstoppable force in the workplace.

In the midst of this explosion of feminine productivity, many women admit they feel uneasy about working; they like or even love their work, but they do not feel at peace about work either. Yet Beaty’s central premise is this:

Every human being is made to work. And since women are human beings, every woman is made to work. (7)

She wrote this book to encourage women to fulfill their calling as image bearers of God tasked with reigning over creation as God’s representatives and reflecting God’s glory in every aspect of culture.

Summary of A Woman’s Place

Beaty starts by reflecting on the various positions men and women hold in the marketplace. In the beginning, God tasked both men and women to work and cultivate his creation. Historically, men have been responsible for most human productivity and control the lens through which our cultures tell stories. Beaty calls for the recognition of women’s contribution to society, as the world fails to flourish if only half of the population follows Psalm 8 and reflects God’s glory in culture.

Beaty starts by reflecting on the various positions men and women hold in the marketplace. In the beginning, God tasked both men and women to work and cultivate his creation. Historically, men have been responsible for most human productivity and control the lens through which our cultures tell stories. Beaty calls for the recognition of women’s contribution to society, as the world fails to flourish if only half of the population follows Psalm 8 and reflects God’s glory in culture.

After her introduction, Beaty provides a brief overview of the women’s liberation movement and the impact of feminism. This is one of the first evangelical books I have ever read that gives credit to this movement for how it has helped women. She writes,

We can be grateful for the choices given by feminism, even if we don’t agree with every choice that every woman makes because of it. (38)

She claims the women’s liberation movement helped women realize that work is an inherent good, and when examining the Bible, we can see it has been good from the very beginning. Perhaps most insightful is her analysis that Betty Friedan’s discussion of “the problem with no name” in The Feminine Mystique is “the pain and frustration that arises when our Imago Dei calls out to us . . . yet we find few creative outlets for doing so” (47). Adjacent to the discussion of feminism, Beaty explores the biblical passages related to work. By looking at Genesis 1 and Psalm 8 she argues that work is good and that God told men and women together to build civilizations for his glory. Work provides value to the worker, but the purpose of work is for shalom.

Beaty provides an historical discussion on work in chapter 4, “Women Have Always Worked.” She argues the concept that men are oriented toward work and women are oriented toward home confuses cultural norms with biblical duty, which brings unfounded guilt and unfounded judgment upon women who work or wish to work. She cites 1 Timothy 5:11-14, Titus 2:3-5, Proverbs 31 and the examples of Lydia and Phoebe to show that women in the Bible were oriented toward the home but the home was the place of industry and economic production.

The Industrial Revolution changed where work takes place and entrenched the idea that “men are to be economic providers and women are to stay at home with children” (103) because work began to take place in the factory or the office rather than the homestead. Beaty also identifies class distinctions in this attitude shift. The upper and middle classes were able to split the spheres of work and life, and thus not working outside the home was a mark of privilege; lower class women had no choice but to work. Despite this paradigm shift, Beaty claims that “no human, male or female, was meant to live a life full of leisure and free of industry” (108).

After dismantling the traditional gender role dichotomy in the first half of the book, Beaty affirms the goodness of womanhood in chapter 5. She claims Western Civilization is entrenched with the idea, even if subtly, that women are less than men. She then addresses the all-encompassing topic of motherhood that so shapes and defines womanhood and influences how, where and why women work. She talks about the fruitfulness of single women, who often find themselves left out of the conversation and wonder what their place is in the church and world.

Finally, Beaty redeems the idea of ambition. Although ambition is often seen as a vice, she encourages women that God wants them to use ambition for his glory and their good (with limitations). It is okay to have dreams and goals and to want to fulfill them, because God placed that drive and desire within us. In the Epilogue, Beaty provides practical suggestions for how everyone (male or female) can equip women for work.

Women are culture makers and have been gifted with skills and talents.

Reflection on A Woman’s Place

A Woman’s Place is refreshing and vindicating. Beaty recognizes the uncertainty many women face in their academic and professional careers. Many women, myself included, wrestle with whether they made the right decision concerning which degree to pursue, when to start and finish school, whether to work full-time or part-time or not at all, and what kind of career to which they may aspire. She assures women that it is okay to want to work, because industry is an expression of the image of God within us. Women are culture makers and have been gifted with skills and talents to use in the marketplace. Beaty’s personal anecdotes were enjoyable and highlighted both the joys and struggles of womanhood. After each chapter she included a short introduction to a woman who is using her gifting to serve God in various professional spheres.

A Woman’s Place has some drawbacks, however. This book may step on some women’s toes. Beaty goes back and forth between praising childrearing and homemaking as affirming culture-making work and asserting that those are not fulfilling vocations, or that they should only be temporary. She cites many homemakers who long to go back to work, but never highlights someone who is not discontent in her homemaking role.

The sample of women Beaty interviewed was skewed toward college-educated upper- and middle-class women, and as a result this book addressed those categories of women the most. This does make sense, though, as Beaty argues the problem of women and work is a primarily upper and middle class issue.

Because Beaty is a single woman in her early thirties, some readers may question what authority she possesses to speak for women who are wives or mothers. But I think Beaty recognizes her limited experience while at the same time championing the idea that women in every stage of life make different decisions and face different challenges. The infighting and so-called mommy wars among women only foster more judgment and guilt.

Lastly, some conservative evangelicals may take issue with A Woman’s Place. Beaty hails from an egalitarian denomination, and she speaks fairly strongly against groups like the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. However, she claims this book does not contradict complementarianism, because she is discussing the role of women in the church scattered, not the church gathered. Although she features a female minister in one of her examples, she does not take a stance on women’s work within the local church.

Conclusion

A Woman’s Place is an excellent book, and I would encourage every woman to read it. However, this book is not only for women. Beaty challenges pastors, professors, employers and anyone who cares about women flourishing in their role as image bearers to read this book as well. Some of Beaty’s statements may push and pull at our assumptions and challenge our vision of the ideal life, but I think those challenges are necessary and appropriately broaden our view of kingdom work.

No comments have been added.