In recent months, we’ve read headline after headline about Facebook’s privacy woes. Each headline stokes a new round of outrage, and each passing outrage brings a predictable cry of do something! What suggestions are given? The most common proposals are some form of government regulation, localizing these social media giants by building a number of smaller networks or encouraging users to just opt out. Normally, the cry of do something! is a five-minute hash-tag fury followed by a period of discussion, and then … nothing.

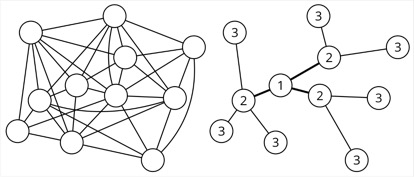

Part of the reason the call to do something is normally followed by nothing is that no one really understands how “social media” works and hence what doing something might look. A good place to begin is by considering the concept of a social graph, which relies on the concept of scale invariance. The structure most networks “naturally” form is a hierarchical tree-like structure, as illustrated below.

These two networks contain the same nodes in the same locations, but their connections have been changed. Note the number of connections at each node in each diagram. On the left, the nodes are highly meshed. On the right, all the connections but a minimal set have been removed. This is what happens in naturally occurring networks. Why?

The basic reason is efficiency. Each node expends some amount of energy and resources in one form or another to build and maintain each connection, and each node in turn also gains some amount of energy and resources from each connection. Each node in the network will reduce its connection count until it receives more value from the network than it puts into the network. A network built in this way is economically efficient in the sense that each participant gains more through membership in the network than they are paying in time and effort to maintain relationships.

Part of the reason the call to do something is normally followed by nothing is that no one really understands how “social media” works.

As a concrete example of how such a scale-invariant network builds up over time, consider a person who brews and sells coffee out of a small street corner cart. The supplier count is likely small, the customer count is small, and connections to local government are also likely minimal. To become more valuable to the owners and the community, the corner operation must grow into a corner shop, inhabiting a fixed physical space. This also means many more customers, connections to a property owner, other business owners, local government, etc. Not only are there more connections, each connection will also likely become deeper. The move from the corner cart to the corner shop means there is more “state” to manage both in the number of connections and the depth of those connections. The value of the shop is directly correlated to its connections into the community, but its connections into the community are limited by the amount of state a single node, in this case a person, can support.

To solve this problem, the business multiplies itself through hiring. Each person specializes not only in a set of skills, but also a set of connections. Hence the shop becomes a mini-network; what appears to be a single node in a larger network from outside is a collection of nodes from the inside. If a single shop becomes a chain of shops, the entire chain may represent a small branch of a network, with a central node connecting to many different suppliers, governments, and customers. Repeat this story thousands (or tens of millions) of times, across time and space, and the familiar tree-like structure of a scale-free network appears.

The brilliance of social media lies in this simple observation: in providing a platform on which to build social networks, the social media site itself becomes both the medium in which the nodes connect as well as a sort of “meta power node” in the social network. As a node within the network, the social media site is not constrained by the same limitations as its human users; the system can support millions of connections, remembering all the state and information needed to maintain all the connections.

As the medium within which the social network develops, the system can harvest the data flowing between every pair of nodes in the network. Using this information, the operator of the network can discover what connections there are, how strong each connection is, what kind of information flows between any pair of nodes and how often and how information flows. The system itself can now “see” what connections “should be there,” or find one person who can influence many others—without its users seeing these things. Further, the social media network can control what each person sees and knows by managing what information is passed through the “meta power node” of the social media network itself.

It is almost as if we have developed a set of roads that not only facilitate communication between the social centers called cities, but the roads themselves can observe traffic, and shift the shape, direction, and destination of any given road based on its observations of the traffic and the designer’s goals. You can be certain at least one of the goals of the system’s operator will always be to maintain the power of the system itself, and hence the operator’s power to make ever-more money off the network they have built.

Returning to the beginning of this article: what sort of something will at least mitigate the harm these kinds of social media networks do, while leaving the good they can potentially do intact? The first answer given above is government regulation. What would such regulation look like, though? Giving users access to their own data? In this context, what the user has put into the network is not nearly as interesting or powerful as the data the network operator has developed about the user by mining the connections between the network’s users. It does not seem to be fair to force the operator to divulge information they have developed, nor does it seem like the data would be useful to individual users even if they did divulge it.

Another form of regulation might be to force these operators to be politically neutral, the way a television station or online publisher might be. How would this neutrality be measured, precisely? Even if you could measure it, can you dig into the algorithms and neural networks used in these social media networks? You cannot really know what is going on “inside” a machine learning driven neural network, so it seems difficult to see how this solution would work.

You could also just opt out. This, however, misses much of the point. These networks have power because they provide economic advantage to the users. Are you willing to give up the increased efficiency and scale social networks bring?

There are no obvious answers to the problem of maintaining the value of these social networks while reducing or eliminating the problems associated with such networks.

Editor’s Note: Future columns on this topic will consider options and explore the intersection between culture and these kinds of technologies more deeply.

No comments have been added.